That left only the codeshare/joint venture on the Tasman, a deal both airlines had felt they needed to make in order to compete with a powerful Qantas/Emirates partnership on Australia-New Zealand routes. This is after all New Zealand's biggest route by far, occupying over half of all its seats. It's always been a highly competitive and - relatively - low priced market, although the edge softened a bit following establishment of the parallel JVs.

Yesterday, Air New Zealand bluntly informed Virgin Australia management that the partnership was at an end, effective the end of the current scheduling period, on 27-Oct-2018. Whether or not Brisbane HQ was aware of the impending axe, there was certainly no prepared media release to explain what would happen after the divorce. Virgin CEO John Borghetti was quoted in the NZ Herald as saying "We thought we were with a good alliance partner and now we won't be", before effectively declaring war on the Tasman.

Other than a continuing, fairly choppy relationship between the two, it's not entirely clear why Air New Zealand jumped. It was pretty much a given that the partnership would have been renewed if they wanted, when it expires in Oct-2018. But the airline's management feels the airline has enough clout to go its own way, particularly with a number of long range A320neos being delivered (it has 10 of them coming this year and next), along with a reasonable amount of slack in utilisation of the widebody 777 and 787 equipment.

Air New Zealand

However, Virgin Australia gives the New Zealand carrier some very vital access behind its Australian gateways. Cam Wallace, Air New Zealand chief revenue officer, said the move was for "purely commercial reasons" seeking to rebut any suggestion of animosity as the motive. But it's well known that alliances don't work in the long run, unless the respective leaderships see eye to eye. And these two haven't for some time. That will make for some interesting discussions, as Mr Wallace is keen to ensure the two airlines continue to codeshare behind the Australian gateways, access that's important for Air New Zealand.

The quid pro quo would mostly be for Virgin to get reciprocal access in New Zealand, but that's not worth as much as Air New Zealand would be asking for.

What happens next?

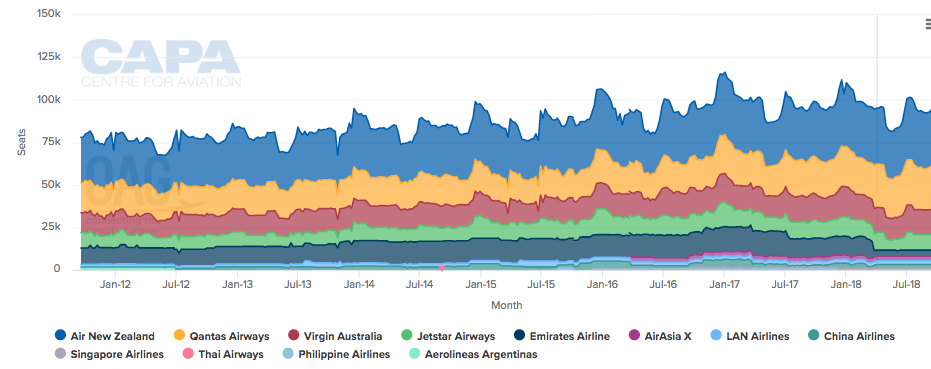

You can get a fair idea of the respective thinking that will be going on by looking at the shares of each airline in the overall market (although specific city pairs are also important in their own right).

Route Capacity Analyser: Australia to New Zealand seats per week, Sep-2011 to Sep-2018

Source: CAPA - Centre for Aviation & OAG

Source: CAPA - Centre for Aviation & OAG

There's no doubt that, across the water at least, Air New Zealand is strong. It today holds about a 35% seat capacity share, while Qantas, Jetstar and Emirates together have a bit over 40%. Against that, Virgin Australia's 15% market share puts them at a severe disadvantage in the market. Where Air New Zealand is weaker is in its beyond gateway access to Australian domestic points.

So Virgin has to move; a rapid expansion of Tigerair trans-Tasman routes is one option; even an unlikely entry to the domestic market, something Virgin Australia has briefly and modestly tried before. Tigerair will struggle in the NZ-origin market as it's scarcely recognised at that end of the route, though its relatively lower cost base will allow it to price competitively.

It does seem likely that Air New Zealand will do a couple of things at least:

- Add in more widebody services on the key city pairs, something it can do at almost marginal cost, where it has any spare capacity (think Emirates operating beyond Australia, to fill in the day its aircraft would otherwise sit on the ground); and

- Establish new routes (and frequencies) on Australia's east coast (and beyond) with its fuel efficient A320s.

Meanwhile, for Qantas, there are pluses and minuses. A fare war is a definite minus, although the combination of a powerful loyalty programme and strong product means it can deliver a premium. Jetstar is more likely to get hurt, with its focus on leisure, if Tigerair enters. A weaker Virgin Australia however does the Group no harm at all, especially if there is no codeshare deal for Virgin in New Zealand, helping give Jetstar's New Zealand operation some breathing space.

Then there's always the background whiff of Air New Zealand's longstanding wish to establish in its own right in Australia - and there's quite a history to that, stretching back over 25 years. Any such motive would be staunchly denied by management, even though the rationale that applied then still exists in spades. It will happen one day, but maybe not just yet.

Will the competition bodies be concerned? Probably not. Even though it hurts Virgin Australia, it will mean there are now three active competing groups in the market, so consumers won't miss out.

Bottom line though: in the short term, there will be blood. And consumers, tourism bodies and airports will be the beneficiaries.