The Trump administration has hinted that the private sector will be invited to play a bigger part in infrastructure investment in the sector though it is still not clear exactly how. Meanwhile rumours abound that the President will focus more on roads, bridges and tunnels than airports in a forthcoming strategic declaration of intent this month.

On the sidelines are crucial issues concerning some of the established methods of raising capital for airport infrastructure such as private activity bonds (PABS). There is a pending House bill to eliminate the tax advantage of PABs, thus reducing their attractiveness to institutional investors. On the other hand there is a pending Congress proposal to modernise the Passenger Facility Charge (PFC), increasing the cap on local PFCs from USD4.50 to USD8.50 per enplaned passenger. So one form of funding might increase, while another decreases.

When considering privatisation, sometimes the municipal and county authorities that own airports in the US are accused of seeking to shore up leaking pension pots or replace other types of infrastructure (such as sewerage) with the money raised from leasing out their airport terminals, rather than making their own contribution to the enhancement of the 'airport experience' for its users . Recent events in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where something of a gamble has been taken with the gambling industry, demonstrate that there is another side to the coin.

Gambling is a big money earner for a number of airports and has been for many years. Airports such as those at Las Vegas and Reno in Nevada and Atlantic City in New Jersey have historically generated impressive revenues from in-terminal gambling activities but they are not alone. Internationally, airports as diverse as Vienna and Singapore were early adopters of this revenue stream and the redevelopment in the mid-2000s of Blackpool Airport in the UK, together with a huge influx of additional air service, was contingent on it being allocated the UK's only 'Super-Casino' slot. It didn't happen and the airport closed to commercial traffic within a decade though it since reopened on a much smaller scale.

It may come as a surprise but the State of Pennsylvania is already the second largest in the US for casinos. In Oct-2017 the State, which is looking for additional revenue sources to plug holes in its shredded finances, authorised a major expansion of gambling, approving activities online, at truck stops and at airports.

As part of the bill, legislators reauthorised the USD12.4 million a year that now goes to the airport for economic development as it has done for the last decade, and to reduce costs to the airlines that use it. Without the reauthorisations, the funding would have ended in the 2018-2019 state fiscal year. Now it will continue into the future unless there is a change in the gambling law.

According to Christina Cassotis, CEO of the Allegheny County Airport Authority, which operates Pittsburgh International, the money will continue to be used to help pay debt service and for economic development, including incentives paid to airlines to start new flights. She added that the fact the Legislature made that choice is a sign "that they are comfortable with how we are administering those funds and what we are using them for."

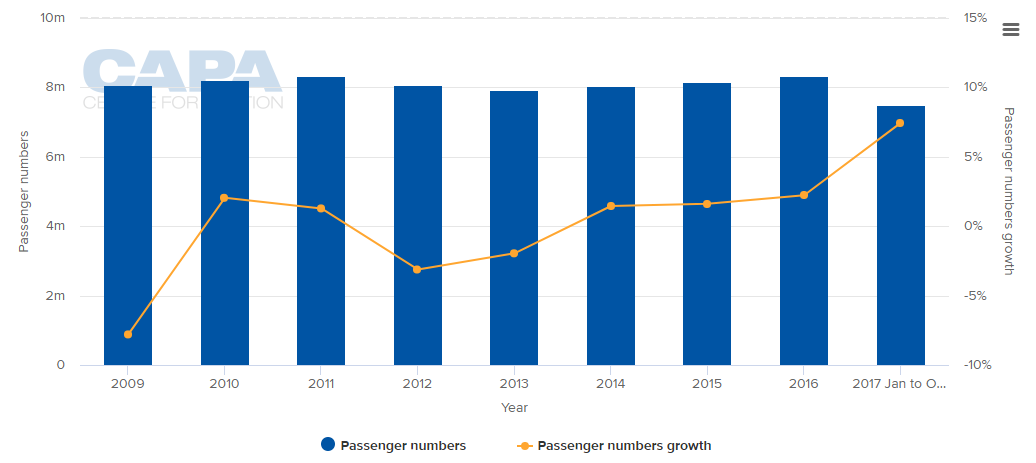

The money was first awarded at a time the authority was struggling to cut costs to the airlines after US Airways closed its Pittsburgh hub in 2004. And there is evidence it has contributed to a slow but noticeable turnaround there, as passenger growth increased by 2.2% in 2016 (the first time such a modest increase as 2% had been achieved since 2010) and by 7.4% in the first 10 months of 2017 (latest available figure).

CHART - Traffic levels at Pittsburgh International Airport grew at a decade high rate in 2017 with passenger numbers up 7.4% across the first ten months of the year Source: CAPA - Centre for Aviation and Pittsburgh International Airport

Source: CAPA - Centre for Aviation and Pittsburgh International Airport

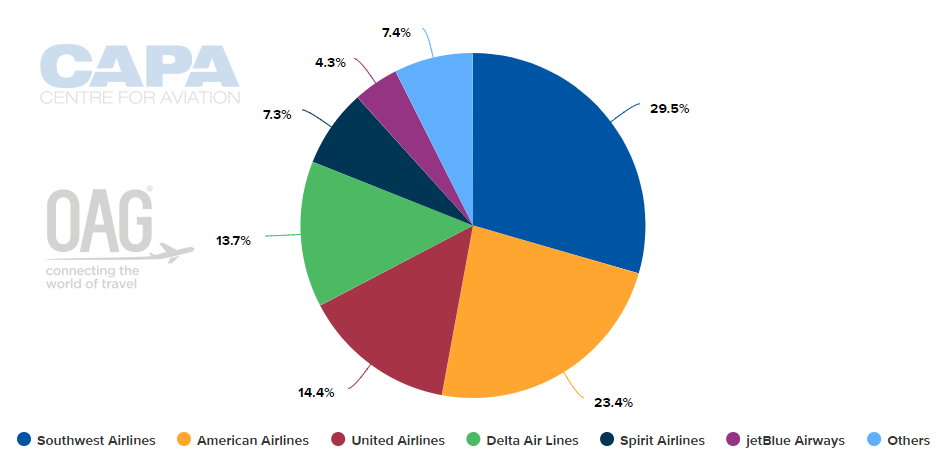

But cash alone is not the answer. There has also been a strategic decision to replace the reliance on a single-carrier hub operation with a more broadly based network of carriers operating with a greater emphasis on point-to-point flights, and led by the doyen of that enterprise, Southwest Airlines.

CHART - Southwest Airlines is the dominant operator at Pittsburgh International Airport and together with number two carrier, American Airlines, account for more than half of the system capacity Source: CAPA - Centre for Aviation and OAG (data: w/c 01-Jan-2018)

Source: CAPA - Centre for Aviation and OAG (data: w/c 01-Jan-2018)

Keep costs competitive for these airlines is an imperative. Few mid-sized airports in the heavily populated east of the US wield much market power and they operate in a congested space.

With much of the airport's debt having been incurred to build the midfield terminal, which opened in 1992, and with the likelihood it will be paid off in 2018, the authority has plans for a USD1.1 billion modernisation that includes a new building for ticketing and security, a new parking garage and a streamlined boarding facility.

Moreover, the authority intends to use the State money to help with the debt on the new bonds needed to finance the modernisation (see the comment regarding PAB's above), which should help to keep costs to the airlines lower since they are the ones responsible for paying debt service and financing the authority's budget through airport rates and charges.

A "small portion" of the money would be used to provide incentives to airlines that start flights to new destinations. In the last year, the authority agreed to pay out up to nearly USD3.4 million in incentives to airlines to start passenger and cargo services both domestically and abroad and it is now chasing down a Seattle flight that could be instrumental to the region's bid to secure Amazon's proposed second headquarters.

Pittsburgh stands to gain from the double benefit of additional revenues from the act of gambling onsite plus accrued earnings from that gambling through taxation that directly benefits the airport itself. Of course there will be those to whom gambling is simply a bad thing. The award of the UK's only 'super casino' licence to Blackpool (and to later East Manchester, which replaced it) for example was thwarted by the intervention of the then Prime Minister Gordon Brown on the basis that regeneration was better than the recirculation of the wages of gainful employment at an unacceptably high and immoral risk.

In that case he may have been right. In Manchester the regeneration money that was provided in lieu of the casino led to the creation of what is now a realisation of Abu Dhabi in Europe at 'Sport City', the City Football Group and all the attached paraphernalia that has transformed a post-industrial slum.

But little of that is appropriate to Pittsburgh, even though it shares a similar industrial history to Manchester. The point is that President Trump will be aware of the 1001 ways in which revenues can be created out of business enterprises in and around any airport and that you can't do the same with roads, bridges, tunnels and rail tracks. It's a no-brainer where the public cash that will be raised through diminishing corporate and personal taxation will be going.