Summary:

- New accounting standards could see more than 50% of the value wiped off the Airbus orderbook from the start of next year.

- Whether a firm order, an option, a MoU, a Letter of Intent (LoI), a commitment to purchase, aircraft manufacturers have always been creative with airline orders.

- New more transparent rules will impact many across the aerospace sector with the timing of revenue and profit recognition significantly affected by the new standard.

But after grabbing all the immediate headlines greater investigation reveals that this order is in fact a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU), and not just one, but four separate ones covering each individual airline. The value of the order also means very little as it is based purely on the advertised list price of the aircraft, and we all know that nobody pays full price in a competitive marketplace and especially a commitment of such scale.

Whether a firm order, an option, a MoU, a Letter of Intent (LoI), a commitment to purchase, aircraft manufacturers have always been creative with airline orders and this is never more evident than when looking at how much each deal is worth. Like all businesses there is a framework for discounting sales and adding special discounts that are based on a range of different parameters. But, revealing the value of orders, with the caveat of 'this is based on list prices' is actually misleading.

The huge order value numbers look good on a press release and in the media, but could be around 50% less in real terms. Airline executives have joked about BOGOF (Buy One Get One Free) deals and better in informal discussions and financial filings have suggested the low unit rates some airlines have paid for historic orders.

You can already get an idea what prices airlines are paying for aircraft when you consider the Airbus and Boeing commercial orderbooks. Based on their latest full year data, Boeing's order backlog stood at 5,700 commercial jet aircraft at the end of 2016, valued at USD416 billion, while Airbus' 6,900 orders were said to be worth EUR1.2 trillion. Even when you take into account the exchange rate the larger orderbook from Airbus cannot explain the significant difference in value.

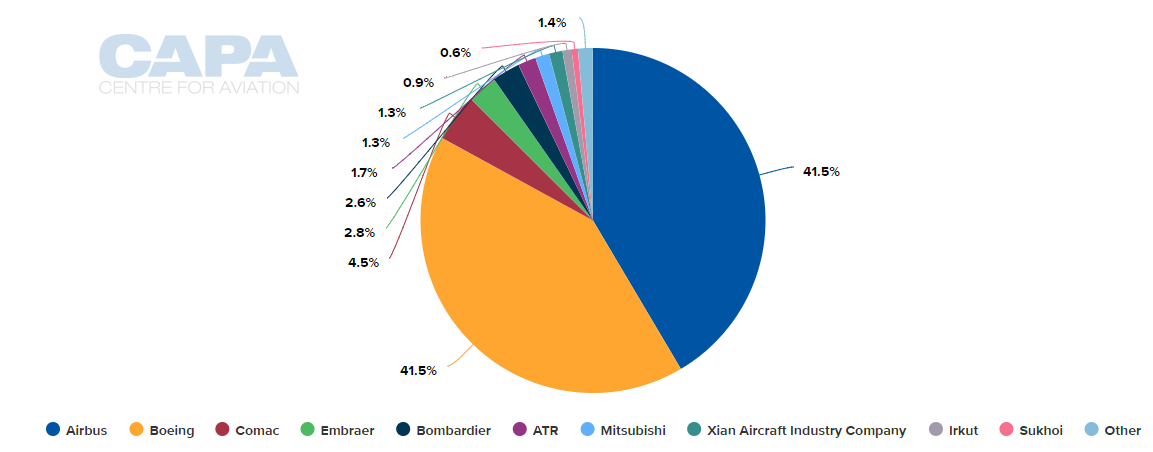

CHART - Airbus and Boeing now equally split the almost 18,000 unit global order backlog each with a 41.5% share of future deliveries Source: CAPA - Centre for Aviation Fleet Database (data: as at 07-Dec-2017)

Source: CAPA - Centre for Aviation Fleet Database (data: as at 07-Dec-2017)

The reason for the difference is actually simple and is purely down to accountancy methods. The Boeing total is based on the price customers actually paid for its aircraft, while the Airbus total is based purely on what it wanted airlines to pay, i.e. the list price for the aircraft. But, this will all change next year and will create a significant loss of its orderbook value for Airbus when new International Financial Reporting Standard IFRS 15 and US Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) ASC 606 are introduced.

IFRS 15 and FASB ASC606 are effective for the first interim period within annual reporting periods beginning on or after 01-Jan-2018 and could see the value of the Airbus orderbook halved as contract values become based on the future minimum revenue it is expected to recognise on each deal. This will likely bring the value of its orderbook down to around EUR500 billion.

The new more transparent rules will impact many across the aerospace sector with the timing of revenue and profit recognition significantly affected by the new standard. Whereas previously when rules allowed notable room for judgement in devising and applying revenue recognition policies and practices, the new rules are more prescriptive in many areas relevant to the aerospace sector.

KPMG says airlines are most likely to experience the impact of IFRS 15 with ticket breakage revenue, through the allocation of revenue between air travel and loyalty points in frequent flyer programmes, with the timing of revenue recognition of ancillary revenues and change fees, and with interline cargo revenue, dependent on whether the airline acts as principal or agent under the new standard.

Engine manufacturers like Rolls-Royce in particular will be hit hard as they will no longer be able to offset the losses made on selling aircraft powerplants by drawing forward the high margin future maintenance earnings. Similarly, loyalty programmes will need to conform to the new methods and American Airlines revealed in a recent filing that it would add a USD5.5 billion increase to liability for outstanding mileage credits and a corresponding USD2 billion increase in deferred tax asset to its balance sheet upon adoption of the new practices.